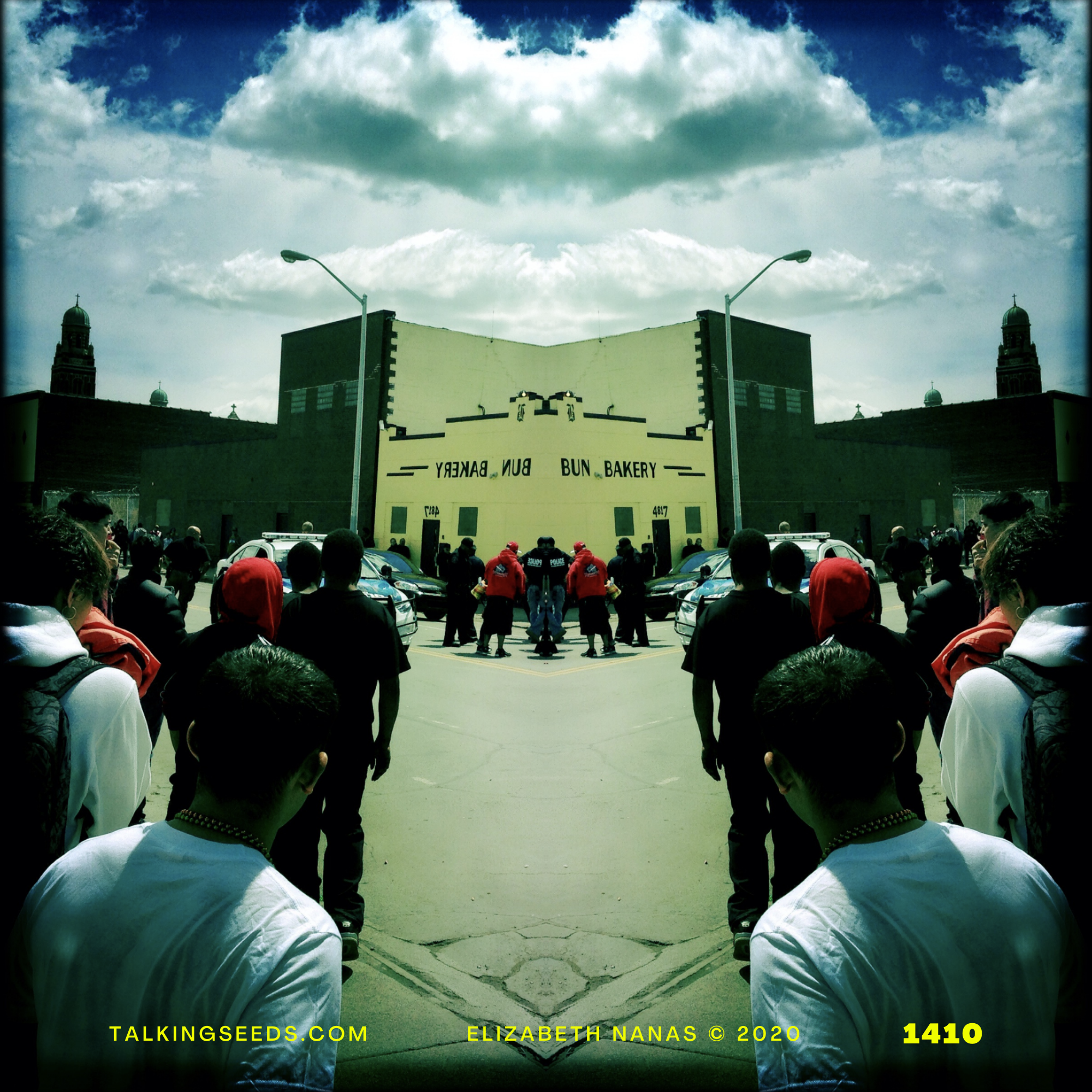

Ethnographic Excerpt:

Just Ghosts

ENANAS © 2021

CINCO DE MAYO 2014

This photo diary captured an hour before and the moments after a teenage boy was shot and killed then his dead body was thrown into the back of a police car. Thoughts outlined here don’t directly reflect that day. This noted, I have been thinking about our neighborhood—its history and potential trajectories—and about locality in the context of this contemporary moment that demands new configurations of community-police-human service systems. Close to seven years later, I am still thinking about the young man whose life was taken as well as all the children, youth, families, and others who, while in a moment of community celebration, were witness to death, departure, termination. He is now a ghost but what does it mean to be ghost?

DANGER

Located two miles southwest of downtown Detroit, “Mexicantown” has been increasingly celebrated by local media as a model place for commerce and community. Hailed for its dense neighborhoods, vibrant commercial districts, (multi)cultural organizations, and strong community networks, the area attracts volumes of suburban and Canadian tourists to its popular shopping and restaurant district. Yet beyond this glorified consumer-class territory, and the gentrified neighborhoods* of Corktown and Hubbard Farms, Mexicantown’s borders are also perceived as spaces of danger.

*By 2021, the boundaries of gentrification have widely expanded since the time of this writing.

PERCEPTION

A May 2006 conversation with my neighbors Kara and Jen illustrates this point by highlighting differences in the ways that people who negotiate the same location construct meaning. These differences in opinions emerged while discussing the escalating hostility between three households in our neighborhood. Over the course of two weeks, there had been several verbal and physical fights that largely revolved around accusations of theft. In our conversations, this violence became the brunt of jokes and the evidence used to justify social positioning claims and identifications. The households who were fighting were each made up of white neighbors who, in this heavily Mexican and Puerto Rican space, appear to be the most impoverished and isolated on our block. Two of the households were, at that time, “known” to be selling drugs from their homes and for having members navigating the informal economy (e.g., sex work, copper-stripping, car battery theft). Further, while gunfire is heard in this neighborhood on a daily basis, none of the informant-residents acknowledged violence, drugs, or sex work as the most serious of society’s problems. Instead, problems considered immediate and pressing to these residents were connected to air pollution, under-employment, lack of access to affordable health care, and decrepit housing.

On the surface, then, it might seem like these residents and the investors who promote revitalization share common dreams regarding the development of this space. However, in neighboring Corktown, revitalization displaced poor white residents who could no longer afford inflated rent prices or the cost of updating their homes to the standards imposed by incoming middle class gentrification (Hartigan, 1999). These stories, of residents forced out of their homes and neighborhoods, become narratives of danger for Vernor-Junction residents who have hopes of improving their lot, yet recognize that “progress” often leaves them behind as they are identified as matter to be pushed away—matter out of place.

PASSING US BY

I can’t stand when they come knocking on my door. Sometimes … I’m like, “Well, I have to do my chores. You gonna help me?” [Imitating the missionaries working in the neighborhood], “Well uh, we just wanna talk.” [Kara continues], “No, cuz if you not gonna help me you’re taking my time. [dramatic pause] Now if you help me, I’ll do it quicker, then I can spare a little time for you. And if you’re not gonna help me, well then, you know what, you need to get the fuck out of my house” (Kara, May 28, 2006).

For Kara, a Puerto Rican born woman renting from a man considered a “slum lord” by locals, Latina faith ambassadors were not compassionate or helpful to her daily needs. Over the years, she has told me many stories about people of faith who she has mocked and critiqued; a self-identified Christian, Kara does not accept that these people of faith are here to do good works.

Some of Kara’s anger seemed to be related to the ways she and her siblings were discriminated against as children for “…being too dark and too poor and too dirty…” (Kara, May 28, 2006). From that time until the present, Kara has felt that her problems with poverty and access to resources were used as evidence of, instead of reasons for, her position in society—evidence that she did not belong, that she was the problem. She resists this interpretation in the ways that she engages and negotiates her dealings with people of faith, even as these missionaries become a more and more common sight in Southwest Detroit, reinforced by the Bush Administration’s embrace of faith-based organizations and “neighborhood healers” to combat local “problems”.

It was in his January 2001 report to Congress, “Rallying the Armies of Compassion,” that President Bush proposed a new role, and fresh start, for government social policy. This role was premised on welfare and social policy reform, the bolstering of (assumed) success of faith-based good works, the renewal of the family and family values, and the rebuilding of “failed” neighborhoods. The Bush Administration’s call to compassionate arms is premised on the idea that faith-based organizations (FBOs) are more intimately tied to failed neighborhoods than are government organizations, and therefore are closer to both the problems and the people—who are necessary Others as both victims and aggressors.

In the Vernor-Junction Neighborhood, Kara is not the only one who views these faith ambassadors with suspicion and rancor—by summer, 2006, neighborhood residents said about these neighborhood healers: They are all hypocrites; They advocate beating women; They are child molesters. Kara and other neighbors consistently challenged these local missionaries, ensuring that their marches through our neighborhood were complicated affairs:

JEN: Here they come, Kara!

KARA: That’s okay. That’s okay. I’ll tell ‘em, we’re, we’re lesbians and … We’re planning the next orgy. And I’ll tell them in English and Spanish.

JEN: No, we can’t mess with them. They have a little kid with them.

KARA: They need to keep their little girl home. I swear to god I’m gonna tell them out loud, “We’re lesbians trying to plan what we going to do tonight.”

JEN: No, they have a little girl with them.

KARA: Well, that little girl better not know the word ‘lesbian.’

ELIZABETH: I think they’re passing us by anyway (Fieldnotes, May 25, 2006).

Recognizable as Latina/o, the faith ambassadors who serve my neighborhood would seem to be precisely the kind of foot soldiers that the Quiet Revolution has in mind—they live close by, they speak the language, they look like the people, and therefore they are close to the problems. But residents of this “failed” neighborhood strongly disagree. These residents are less concerned with messages of hope than with material benefits that may be gained through meaningful employment and access to health care and education.

Yet, progressive policies designed during the last century—during an intense push to promote access to employment, health care, and education—are increasingly under attack by neoliberal policies. While the WHFBCI seeks to become more inclusive of faith stakeholders, other classes of people and communities are increasingly under attack and targeted as matter to be regulated.

One time they came by and me and Ricardo were sitting there and the door was open and they were like, “Hi, how are you?” And I’m like, “There’s nobody home.” And they’re looking at me, [like] “Well you’re here.” [Well], “Nobody’s home. We’re just ghosts.

Locality may be realized within the neighborhood, but this realization is limited because the resources and barriers we engage and negotiate require a sort of flexibility whether consciously understood or not. Both Jen and Kara rarely leave the neighborhood or travel more than one mile to work, shop, socialize, or conduct other daily business. At the same time, this limited modality does not mean that the resources Kara and Jen draw upon are limited to the neighborhood. Each of us are also flexible, global citizens in our own ways.

Kara’s identifications with citizenship, family, and racial ideologies are fluid through a conscious understanding of these categories as permeable. Thus, it is important to know and respect your roots, but your belonging is not limited to what others decide (whether family or nation-state)— imagined possibilities of belonging can be both located and dynamic. As a flexible citizen, Kara navigates dynamic and liminal spaces, even going so far as to invoke the identity of a ghost— transparent and ethereal, haunting the edges of citizenship and belonging, being and dreaming.